Jenny & Sophie: The Text Became Art, Inside Turned Out

As my month as resident-reviewer here comes to a close, I want to look at something different. I want to return to two artists whose relationships with words have affected my own approach to poem-making: Jenny Holzer and Sophie Calle.

True story: eight years ago I met the artist Jenny Holzer in a large format Polaroid studio in Manhattan. She’d invited my friend to pose for photographs that would be sold in an auction. The year before, I took him to UC San Diego’s campus to see Holzer’s Green Table—a large granite picnic table inscribed with her texts. He fell in love with her work and wrote to her agent, requesting that Holzer commission a tattoo for him. YOUR MODERN FACE SCANS THE SURPRISE ENDING is the text he chose to have permanently inked across his ribs. In the New York Polaroid studio, Holzer was quick and deliberate, instructing Jesse where to stand and guiding the photographer on how to frame each shot. The ending of this story is a dream come true: I was in a room with my favorite living artist, a woman I’ve idolized for years, watching her document her own art. So, it was no surprise that my modern face stared up at hers blankly. I was unable to articulate a single coherent sentence in her presence.

Holzer is a conceptual artist who uses subversive, passionate, politically-charged, disturbing text and displays it via a variety of media, including marquees, billboards, LED displays, marble, wood, and Xenon projections. She is perhaps best known for her Truisms, an alphabetical list of contradictory phrases that sound like cliches or common myths, but were actually penned by Holzer herself. In an essay by David Joselit, he refers to these one-liners (PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT; MONEY CREATES TASTE; RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY) as “conceptual readymades.” Besides the Duchampian use of text, what I love about Holzer’s language is how the voice can be both individual and collective, dislocating facts and ideas that seem to come from a variety of sources. It is somehow alienated and depersonalized, yet remains authoritative. In Inflammatory Essays (pictured above), Holzer employs many different I’s and You’s, but the speaker is always undetermined. When I was a study abroad student in Italy, I remember a black and bronze plaque hanging just above the drinking fountain in an art museum. It read:

Joselit explains that Holzer’s “model of authorship” is based on outside ideals or concepts that become internalized, and then “turned inside out to make art.” These are essentially “internal monologues as public speech.”

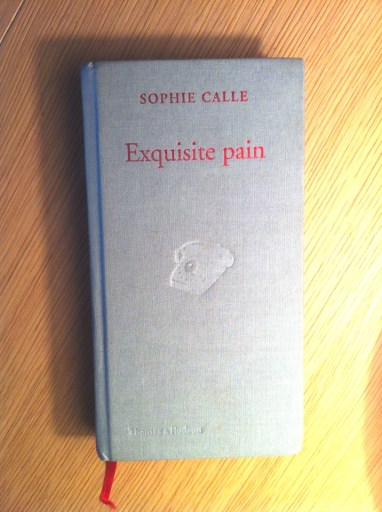

Where Holzer creates public speech with an authorial voice that is collective, French artist Sophie Calle externalizes the internal, revealing intensely personal experiences with text and image in public spaces. The bits of information build a narrative that at first glance could be scraps from Calle’s diary, but the story is told with an emotional distance in an overall expository, detached tone.

I saw Calle’s Douleur Exquise (Exquisite Pain) exhibit over a decade ago at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It is a story of heartbreak documented through photographs and text, beginning with this description:

In 1984 the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs awarded me a grant for a three-month scholarship to Japan. I left on October 25, unsuspecting that this date would mark the beginning of a 92 day countdown to the end of a love affair. Nothing extraordinary—but to me, at the time, the unhappiest moment in my life…

Calle counts down the “Days to Unhappiness” with photographs, plane tickets, memorabilia, diary entries, and scraps of remembered conversations up to the moment she was abandoned by her lover—she waited for him in a hotel in New Delhi, but instead of meeting her, he called to say he’d fallen in love with someone else. The photograph of the red telephone, the one she spoke to him on, is the final image that flags a movement from grief to recovery, dividing the artwork (and book) into two sections. It is in the second section (“After Unhappiness”) where we witness an evolution take place inside the artist:

…whenever people asked me about the trip, I chose to skip the Far East bit and tell them about my suffering instead. In return I started asking both friends and chance encounters: “When did you suffer most?” I decided to continue such exchanges until I had gotten over my pain by comparing it with other people’s, or had worn out my own story through sheer repetition.

Calle repeats her breakup story ninety-nine times on one page beneath the photo of the red phone and places it beside the story of a stranger’s most painful memory on the other page. With each entry, the details of her obsessive retelling begin to diminish. The text literally fades until the ninety-ninth page is blank, nothing but black paper below the photo of the red phone on the white hotel bed. Through the repetition and juxtaposition of her own grieving with the pain of others, she allows herself to heal.

These artists are creating works of art. But they are also poetry, too. Both Holzer and Calle play in a region where the two pursuits overlap, where text becomes art, where inside is literally turned outside for us to see, to read, and to experience.